(For 2015, I am trying to avoid playing any games or consuming any static media with zombies in them. My reasons, and other fun things like ‘what exactly counts as a zombie?’, are explained here.)

I’m definitely in a slump when it comes to enthusiasm for digital games. It is not unusual for my enthusiasms to go through phases, and right at the moment tabletop RPG is a lot more exciting to me. Having so many videogames off-limits is definitely a contributing factor, though.

I was honoured to be on the jury for this year’s WordPlay showcase, spotlighting writerly games. None of the ones I covered contained zombies, huzzah; results to be announced in November. Last year’s showcase featured things like A Dark Room, Horse Master, With Those We Love Alive, Coming Out Simulator, Choice of the Deathless, Elegy for a Dead World and 80 Days, as well as my own Invisible Parties; as a shortlist of ‘notable things that have happened in texty games recently’, it’s as useful (and as inevitably incomplete) as the XYZZY nomination list, which is why it’s cool to have multiple things in this arena. Things that I already knew, but which this really confirmed: juried events are pretty draining, and I have really high expectations of what constitutes ‘good writing’ in games.

I went to all four days of PAX Prime, largely to facilitate storygames (in my case, Night Witches and Microscope Union). But I did do the obligatory wander around the expo floor in order to get stressed out and be reminded about how hilariously uninterested and/or out-of-touch I am with 97% of gaming: and in that time I only saw one game that was really pushing itself as zombie-based, and that was a brief clip in a montage thing in the Indie Megabooth and I couldn’t have identified it if I wanted to. I dunno if that’s hopeful, or just the artefact of a very superficial sampling method.

Avoided

Trapped in a Room with a Zombie, from Room Escape Adventures. Seattle’s live-action room-escape scene has expanded somewhat in the past couple of years; I’ve enjoyed Puzzle Break‘s offerings in the past. While Puzzle Break feels like a hand-crafted labour of love, Trapped is showing in over twenty locations in the US, and its marketing feels skeevy. Quoth The Stranger:

They have an actor dressed up like a zombie. That’s pretty much the whole theme, and they milk it hard. If you like zombies, you might like this one more than I did.

So I guess that part of the challenge is that, in addition to solving puzzles to unlock the door, there’s an elimination mechanic with a slow zombie that crawls about trying to get you. The problem with this scenario: the most obvious solution is to do the zombie in with a blunt instrument and then rifle its pockets for puzzle pieces.

Eldritch Horror, a board game that strips down the vast shambling mass that is Arkham Horror into something that doesn’t require an intimidating chunk of time and table-space. A friend had taken me on a canoe trip, and invited me to dinner and board games afterwards; I had already explained my zombie thing, and was quite content to sit quietly, nurse my aching arms and drink cider while they finished up a half-done Horror game, since I hadn’t seen Eldritch played before and was mildly curious. Both Horrors feature zombies as an occasional low-level monster, slightly tougher than Cultists but only a threat to the least combat-ready characters. I don’t know that I would have had the bandwidth to learn a still-somewhat-complicated game at that point, so having a reason to sit out was not unpleasant.

Eldritch Horror, a board game that strips down the vast shambling mass that is Arkham Horror into something that doesn’t require an intimidating chunk of time and table-space. A friend had taken me on a canoe trip, and invited me to dinner and board games afterwards; I had already explained my zombie thing, and was quite content to sit quietly, nurse my aching arms and drink cider while they finished up a half-done Horror game, since I hadn’t seen Eldritch played before and was mildly curious. Both Horrors feature zombies as an occasional low-level monster, slightly tougher than Cultists but only a threat to the least combat-ready characters. I don’t know that I would have had the bandwidth to learn a still-somewhat-complicated game at that point, so having a reason to sit out was not unpleasant.

Zombies, though not by that name, are a pretty well-established element of the Lovecraft canon; Herbert West – Reanimator is a retread of Frankenstein with the monster just straight-up monstrous, and makes a pretty good summary of how Lovecraft was mad racist.

Their outlines were human, semi-human, fractionally human, and not human at all—the horde was grotesquely heterogeneous.

Interesting distinction here: in many works, zombies are scary because they represent loss of individuality, subsumption into the crowd. That’s not Lovecraft’s fear: he isn’t really troubled by the idea of becoming one of these things at all.

Quit

Halfway. A tactical turn-based shooter along similar lines to Space Hulk. The heroes are stuck in a spaceship to which Mysterious Badness has happened, and most of the crew are now hostile and weird. It isn’t clear that they’re really mindless – they shoot electricity and make tactical use of cover and stuff, so it is at least plausible that they are more Borg than zombie.

But in this case, I just didn’t care enough to stick around long enough to find out, not with the possibility that finding out might very well require me to ditch. The mystery drags on for too long for such a stock device, the characters are boring, the combat falls into that turn-based trap where most fights are just attrition slugfests.

The Curious Expedition. An exploration-roguelike in which you play Doyle/Verne Victorian explorers competing for fame and glory while avoiding being eaten by tigers. It’s sort of FTL-inspired and very boardgame-ish. Nice job on female PCs, not so sure about Generic Natives. Has some decent opportunity-cost/Minesweepery-calculated-risk tactics. Fun.

There are plenty of fantastic elements: velociraptors stalk the jungles, and raiding ancient temples usually results in curses. And sometimes your party members can get turned into hideous Abominations. Abominations are good at fighting and carrying loads. Normal human party members can make quips at you, acquire personality flaws, express preferences, and appear to have business of their own sometimes. The Abominations sometimes eat your donkey. Or turn on you if you try to stop them. It’s a zombie. God dammit, I was really getting into this!

There are plenty of fantastic elements: velociraptors stalk the jungles, and raiding ancient temples usually results in curses. And sometimes your party members can get turned into hideous Abominations. Abominations are good at fighting and carrying loads. Normal human party members can make quips at you, acquire personality flaws, express preferences, and appear to have business of their own sometimes. The Abominations sometimes eat your donkey. Or turn on you if you try to stop them. It’s a zombie. God dammit, I was really getting into this!

Starbound. I bought this almost entirely because I was in the mood for Terraria, which has zombies from the outset. I did my research: the only mentions of zombies were from people who wanted zombies in the game, or in a mod. Starbound has some nice features – it’s more about the set-pieces than Terraria is, which is both good – story missions! – and bad – the set-pieces tend to be very traditional-platformer fare, with precision jumping or tough bosses. For some folks I’m sure this is amazing; I hate precision-platforming and am pretty damn ambivalent about bosses who can only be defeated by a specific pattern. One of the things I like about Terraria is that if a boss is too tough, you can usually build an arena in advance to fight it in. In Starbound you’re probably encountering that boss in an unmodifiable mission area.

Anyway, I was settling into the early game, idly considering how I was going to lay out my first sprawling colony while knocking off the Get The Basic Things missions, when I hit a Mysteriously Silent Mine where all the ship fuel was produced. It was predictably overrun by monsters. Pink, blobby, tentacle-faced things. I started rescuing pockets of trapped miners, all wearing miner helmets and high-visibility vests. Then I started encountering tentacle-faces wearing the same helmets and vests. Oh, yawn.

The most annoying kind of zombie, for purposes here, is the Strung-Out Mystery Zombie: probably something kind of zombie-ish, but the story keeps you in suspense about the details of its crushingly routine plot. To cap it off, a pretty tough boss fight appeared around this point – well, OK, it wasn’t exceptionally hard if you had good enough healing items, but in a really bad instance of Minecraft-death design, if you lose the boss fight you have to play the entire level again.

So, once again: do I beat my head against this boss fight, when my reward for winning it is probably going to be ‘yes, they’re basically zombies, stop playing now’? The only thing that makes a boss fight worth it is the prospect of more stuff afterwards – story, cool gear, leveling up, new areas. The crappiest boss is the final boss, because all you get is a (probably lacklustre, because endings are difficult) ending.

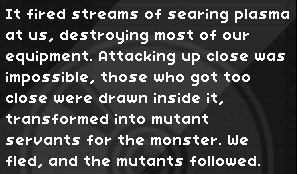

Nonetheless, I stuck it out. Yup: pessimism entirely justified. The big crystalline eye monster thing had turned the miners into mutant servants. No mitigating factors arose. Former humans, still human-looking, capable only of violence and servitude. Zombies.

Which was really a pisser, because… well, shit. This is an expensive habit, if nothing else. I’ve bought several games largely because I can’t play a game that I’m in the mood for and already own, and then I find out I can’t play the substitute either.

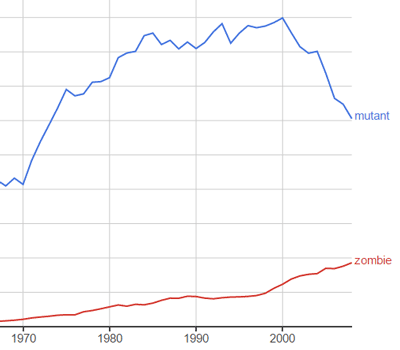

Mutants were kind of a thing in the 80s and 90s. Observe this ngram:

The peak year can move about a bit, depending on smoothing and corpus; and the scientific sense of ‘mutant’ mean it’s kind of an apples-to-oranges comparison. Still: mutants became kitsch. (Fallout‘s Super Mutants feel like an embarrassing relic of the steroid-oozing 90s.) I think, alas, that has less to do with being overplayed than with the social concerns they drew from: nukes, mostly.

*

Let’s return to that thing about disgust as social exclusion. Last time I talked about the role that disgust plays in in-group hierarchy; but in-group hierarchy is almost always related to how out-groups are defined, and vice versa.

As previously mentioned, the primary, cross-cultural objects of disgust are faeces, other body fluids, rotting meat and corpses. When a sense of disgust develops in early childhood, an important early pattern to emerge is the concept of contamination – the idea that contact with a disgusting thing can render other things disgusting. The common thread is obvious: these are the most common vectors for parasites, disease, and food poisoning. The fundamental purpose of disgust is to keep you away from things likely to make you sick.

The biggest vector for getting sick, of course, is contact with other humans; we also tend to find symptoms of disease disgusting. But we also generally go beyond that: we extend our sense of disgust beyond literal sources of contagion into other categories of social undesirability. Disgust lends moral claims a visceral strength that they might otherwise lack; the average medieval peasant might not have seen what was so wrong with a heretical formulation of the dual natures of Christ, but throw in some weird ritual butt stuff and now you’re talking.

Mind-body dualism, of a type that despises the body, runs deep in Western culture. Early anthropometry tended to emphasize the animal corporeality of foreign, low-class and criminal bodies, while depicting northwestern Europeans as akin to classical sculptures animated by souls. And disgust at the political scale has historically been a justification for violence and atrocity. Outsiders must not just be seen as bad, but nauseating. They smell; they are dirty; they eat repulsive things; their customs break taboo, particularly with regard to sex; physical difference is exaggerated into grotesque deformity. They are scarcely human. They are equated to particularly reviled kinds of animal, or to disease itself. They want to contaminate you. And if their actual members don’t match up to this image, they can be made to.

In Typing of the Dead: Overkill, the conventionally attractive human heroes are contrasted with zombies which go for maximum physical distortion, including a wheelchair-bound quadriplegic and a full level devoted to circus freaks. Typing is, of course, aiming to be in the worst possible taste – a difficult honour to aspire to in a medium that has spent the past eighteen years with a teenager’s idea of a Tarantino movie as its highest aspiration.

In The Last Stand 2, a good number of the zombies are fat. On its face, this isn’t unrealistic – the game’s set in contemporary America, where a considerably higher proportion of people are obese than are usually represented in games and film. What’s unrealistic is that fat zombies are very distinct from the general population: there are Normal Zombies and Hugely Fat Zombies, and nothing in between. (One of them is a recognisable parody of Michael Moore; why he’s in there isn’t articulated, but given the game’s survivalist gun-nut aesthetic you can probably take a guess.) This is obviously a relation of beat-up-a-celebrity games, and of burning in effigy.

(By contrast, The Walking Dead features zombies with a pretty broad range of body shapes – sometimes it even becomes relevant, as when Larry’s sheer mass makes the prospect of him turning more of a threat. But they’re not treated as a separate class, or as inherently more disgusting; normally it’s not flagged up at all.)

Fat Zombies are a pretty regular trope in zombie games. They’re slow-moving, take a lot more bullets to stop, and their vast guts sometimes explode when they’re killed. Fat-hate is more broadly acceptable than many other forms of bigotry, it’s easy to represent, and it matches up well with the zombie’s role as an externalisation of our icky, fallible, inescapable corporeality.

It strikes me that many gamers buy games at a far higher rate than I am used to. Having grown up in a household where such things were frowned upon, I went down the force-of-habit route rather than the defiant-splurge route, and anyway a combination of AAA-incompatible taste and propensity to obsess over a single game make that the path of least resistance.

On a different tack, what about zombies that can be dezombified? I downloaded GW2 the other day — an acquaintance who’s a big fan passed on the news that it had gone F2P — and discovered that one of the “races” starts out in an area with a lot of undead. I was pleasantly surprised that there were a fair amount of nonviolent quest-fulfillment options (play with puppies! “revive” NPCs! treat “evil” things with kindness in order to turn them away from the path of evil!); however, the actual undead must apparently always be killed. The very presence of a non-zombifying “revive” mechanic was an interesting contrast to the hordes of intractably hostile undead. Even more so when you start on narratively zombielike beings rather than “reanimated corpse” zombies — thralls and so on, I mean, who may still count as alive.

Ooh, that hit a memory button — Urban Dead! Do you remember UD? Did you ever play it?

It strikes me that many gamers buy games at a far higher rate than I am used to.

Well. OK. The stats – at least on Steam – suggest that you’re in the majority, rather than otherwise. Most Steam accounts own very, very few games; the people who own lots of games and buy more semi-regularly are a pretty small minority (and Steam gamers are a minority among PC gamers, who are a minority among gamers generally…)

My zombie definition requires ‘at least semi-permanent.’ If de-zombification is easy, or routine, or commonplace, then we’re really more in mind-control, or else werewolf / Jekyll & Hyde territory, aren’t we?

I recall playing Urban Dead quite briefly – pretty much up to the point where it became clear that you couldn’t accomplish very much in the game without (somewhat) large-scale organisation in external forums, which I didn’t have the first idea about.

I was fascinated by your discussion of disgust. How would you frame the modern disgust (yet cognitively dissonant desire) of the excesses of celebrity or pure mind-to-mind disgust of Reddit shenanigans? There’s sometimes a physical aspect to that (excessive plastic surgery or gore pics) but often it’s just the moral or intellectual disgust.

Is there a zombie equivalent to this sort of disgust?

OK. So I think that most modern celebrity-related scandal stuff is about shame, not disgust. If a celebrity semi-accidentally drops a sex tape or snorfles up a bunch of drugs and does stupid shit, that’s generally shameful but not disgusting.

I’m not quite sure what you mean by ‘pure mind-to-mind disgust of Reddit shenanigans’ – this is a topic that’s hard to discuss without concrete examples! But if you’re thinking of gore pics or the kind of harlequin-foetus/goatse.cx stuff that circulated on rotten.com, that’s pretty clearly an instance of disgust as adolescent status-contest / proving-ground, of the type which I talked about here.

My three major sources on disgust, if you’re interested, are Raymond Geuss’ Public Goods, Private Goods (which is mostly a political philosophy work about the permeable barrier between public and private), Martha Nussbaum’s Hiding from Humanity (mostly a philosophy-of-law work with heavy reference to psychology) and Gary Faigin’s The Artist’s Complete Guide to Facial Expression (a practical drawing guide organised along psychology lines.)

Pingback: A Year Without Zombies: Envoi | These Heterogenous Tasks