Hanako Games’ latest is a time-management game in which the student council at a posh girl’s school acts as a detective force, solving mysteries, intervening in conflicts between students, and preserving the school’s reputation. You play Elsa Jackson, student body president, assigning your minions on the council to deal with crises around the school. While it’s up-front about being a yuri (lesbian romance) piece, the sex content is mostly innuendo and fades to black. There’s a little bit of magic – a crystal ball that gives you a perception boost, a hint of Lovecraftian badness at the world’s edge – but Magic School is not what the story is about at all.

Hanako Games’ latest is a time-management game in which the student council at a posh girl’s school acts as a detective force, solving mysteries, intervening in conflicts between students, and preserving the school’s reputation. You play Elsa Jackson, student body president, assigning your minions on the council to deal with crises around the school. While it’s up-front about being a yuri (lesbian romance) piece, the sex content is mostly innuendo and fades to black. There’s a little bit of magic – a crystal ball that gives you a perception boost, a hint of Lovecraftian badness at the world’s edge – but Magic School is not what the story is about at all.

Like Hanako Games’ earlier Long Live the Queen, the early experience of Closet is intimidating: situations that you don’t really know how to handle, time getting away from you, a sense of flailing against punishing difficulty. Once you learn it – which is, alas, largely a matter of figuring out and then remembering the possible outcomes for all the repeating mysteries – it becomes more gentle, but it’s never trivial.

Mechanically, it’s quite board-game-like, and is presented as such, with characters shown as cards or tiles, and literal d20 rolled:

The metaphor’s balance is a bit odd, though; in the normal difficulty mode the dice are loaded in your favour. Why load the dice instead of lowering the challenge level? The former, honestly, will probably make players happier when you’re adapting a board-gamey mechanic to a computer game, because humans are terrible at estimating probability, and will get irked if a 9-in-10 chance doesn’t succeed 99% of the time.

The art is a notch or two shinier than the Hanako games I’ve played recently, although there’s some slight unevenness. The digitally-painted cutscene art doesn’t quite feel linked with the more anime-styled portrait art: in particular, Althea – who has a strong-lined face with a confident, knowing range of expression – looks like a completely different person in the cutscenes. And the hand-crafted characters are clearly distinct from the randomly-generated minor NPCs – though there’s an option to render the major NPCs in the simpler style. (Indeed, if you want you can switch on the custom campaign, which removes most of the character-oriented plot and lets you put your own character portraits into the game.)

A lot of things about the game put me in mind of Dangerous High School Girls in Trouble, but where Girls is straightforwardly about rebellion, about fixing a corrupt system by exposing secrets and acting out, Closet deals with more complex, compromised motives. Closet is a game about being a police force or intelligence agency – and not, importantly, one with any particular incentive to defend justice. Following the Long Live the Queen formula that the stuff you care about is the stuff that saves you from Game Over, you’re watching out for your hit points: if the school’s Reputation is too damaged by scandal, you’re booted out. You also get scapegoated if the council’s Karma runs out, but Karma is really just a more internal version of Reputation: it’s about how the student body sees you, so it’s as much about whether you get caught as whether you’re actually doing things that are unduly cruel, creepy or oppressive.

From the outset, the story pulls you in lots of different directions. Elsa has personal goals, responsibilities to her friends, institutional duties, ethical qualms about treatment of classmates – these sometimes align, sometimes tug in different directions. As with Long Live the Queen, the early game strongly encourages you to focus on self-preservation. The cool thing, though, is that this never entirely dominates nor goes away. It’s probably not tenable to be a squeaky-clean paladin; but nor does the game demand a total conversion to cold-hearted ruthlessness, though it constantly dangles that possibility before you. The game, then, hits a sweet-spot of genuinely tricky choices in a way that most Big Decision games fail at. Again, the formula is conflicting goals that genuinely matter, and that do so organically rather than in contrived dilemmas.

For instance: when the game begins, it’s revealed that one of your minions is a traitor (echoes of Werewolf here) who will try to sabotage your efforts. If you earn the traitor’s loyalty before she strikes, she confesses beforehand and you can opt to forgive her and keep her on your council – which makes life considerably easier in the long run, because playing with fewer minions is considerably tougher. But as far as I can tell, this only succeeds if you also initiate romance with them – which is a pretty compromised basis to base a relationship on. The council are Elsa’s friends, but they’re also her tools, and it’s an open question which matters more. Even when your goals align it creates a question-mark.

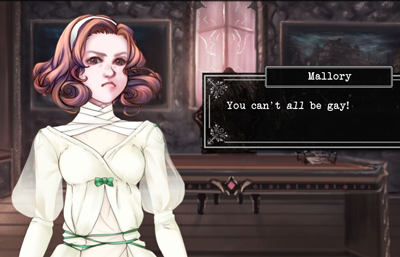

NPC agency in romance games has been a subject of some discussion lately; and Hanako Games has long adopted a stance of strongly-defined characters, PCs and NPCs both, who aren’t hugely malleable to the player’s desires. One council-member is indelibly straight, and the most you can hope from her is snuggly platonic friendship. The others mostly have pre-existing history with you which necessarily shapes any relationship you choose to pursue – meaning that some relationships make the game considerably harder. Similarly, the game has a fairly strong idea of who Elsa is, although that emerges subtly: tall, cool and collected, a top in bed and out of it, not a million miles away from a high-school version of Shepard.

NPC agency in romance games has been a subject of some discussion lately; and Hanako Games has long adopted a stance of strongly-defined characters, PCs and NPCs both, who aren’t hugely malleable to the player’s desires. One council-member is indelibly straight, and the most you can hope from her is snuggly platonic friendship. The others mostly have pre-existing history with you which necessarily shapes any relationship you choose to pursue – meaning that some relationships make the game considerably harder. Similarly, the game has a fairly strong idea of who Elsa is, although that emerges subtly: tall, cool and collected, a top in bed and out of it, not a million miles away from a high-school version of Shepard.

The game also doesn’t lead with Elsa being black (with short, natural hair), or shove it to the forefront of the narrative; she doesn’t appear on the cover. But race certainly pokes its head in at a few points. It’s the underlier to Elsa’s precarious position; she’s told point-blank that if she fails in her duties she’ll make an easy scapegoat, not being from one of the prominent families that mostly populate the school. When her teachers manipulate her via university recommendations, the fictional stand-in for historically-black Howard University (here it’s Packard, nice touch) is a lot more likely to believe that she’s being screwed with. Similarly, this Christian high school seems to be treat lesbian relationships with an attitude of benignly looking the other way – until someone has a reason not to. An awful lot of the game is underpinned by the reality that as a queer black woman, conditional tolerance easily becomes a weapon to be used against you.

(The game’s title is a reference to the cabinet noir, the French term for secret mail-interception / cryptanalysis agencies; but that’s usually translated as black chamber or black room, so the pun is probably no accident.)

There’s a nice expectation-reversal moment with the minor NPCs. For most of the game, you’re getting events about generated characters. Their faces, stats, names, problems are clearly determined at random; their lower-quality art style sets them visibly apart from the major, hand-crafted NPCs, and this reinforces the sense that you have no persistent relationships with them, and no prospect of forming any. They disappear after you resolve their cases; their problems are variations on a pattern, not unique. The game’s mechanical rhetoric strongly encourages you to regard them as disposable.

But then in a later, crucial, unique case – one which takes a long time to resolve, and can end the game if you don’t deal with it quickly enough – some of those generated characters, who you probably assumed had been discarded after their stories stopped being important, start recurring. They remember what you did to them, good or bad, and this affects how willing they are to help you out. This only really happens once, but it’s an effective moment.

*

On the same day that Black Closet was released on Steam, social media lit up with news of Ahmed Mohamed, a 14-year old Muslim boy who’d been arrested two days before after bringing a home-made clock to school to show his engineering teacher. It was a perfect shitstorm for the school authorities. Mohamed was so obviously innocent, so transparently the victim of prejudice, so perfectly fitted to the Black Twitter zeitgeist yet so respectable and nerd-sympathetic; his family and classmates were savvy and effective in their use of social media, while the school was sluggishly, defensively tone-deaf. Prominent figures in politics and tech lined up in Mohamed’s support, their endorsements implicitly damning the school.

So playing Black Closet with all that going on in the background felt oddly apropos. You’re presented with an unclear situation, you don’t really have all the facts, you probably don’t have the time to get them. You don’t care too much if you brutalise a few kids, or look a little bad, in the process. Sure, it might be nothing, but you’ve got to control the situation; you have to do something. And sometimes it dawns on you, not very far into the process, that the kid you’re dealing with is almost certainly harmless, that there’s a very good chance that you’re fucking up their life purely to save face, or preserve the feelings of anxious conservative parents. And you’re so focused on winning this one, on defeating this challenge, you’re so locked into a pattern of regarding your charges as potential malefactors, that you push the button anyway.

Pingback: Black Closet (Hanako Games) | Emily Short's Interactive Storytelling